Further reading:

IPCC (2023): Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Klein, N. (2014): This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. Simon & Schuster.

Wallace-Wells, D. (2019): The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming. Tim Duggan Books.

Problem Background

The CLIMATE CRISIS refers to human-driven changes in Earth’s climate, primarily from greenhouse gas emissions, leading to severe environmental, social, and economic impacts. It manifests through rising temperatures, biodiversity collapse, and extreme events, threatening global stability. It provides the urgent backdrop for frameworks like Planetary Boundaries, Earth4All, and Doughnut Economy, and fuels debates between Green Growth and Degrowth. Addressing it requires Systems Thinking, Resilience Thinking, and Transition Design for systemic responses. The crisis also makes Climate Justice and Global Governance essential for equitable and coordinated solutions.

Further reading:

Newell, P., Mulvaney, D. (2013): The political economy of the just transition. Geography Compass, 7(5).

Heffron, R., McCauley, D. (2018): What is the Just Transition? Geoforum, 88.

Schlosberg, D., Collins, L. (2014): From environmental to climate justice. WIREs Climate Change.

Problem Background

CLIMATE JUSTICE frames the climate crisis as a question of equity, recognizing that those least responsible for emissions are often most affected. It demands fair distribution of costs and benefits, addressing vulnerabilities across gender, race, and geography. The concept of Just Transition ensures that moving to a low-carbon economy creates decent work and protects communities. Together, they connect with Development Cooperation, Stakeholder Engagement, and Eco-Social Innovation to design inclusive transformations. Climate Justice also complements Transition Design and Wellbeing Economy by embedding fairness into systemic change.

Further reading:

Rockström, J., et al. (2009): A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461.

Steffen, W., et al. (2015): Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347.

Richardson, K., et al. (2023): Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries. Science Advances, 9(37).

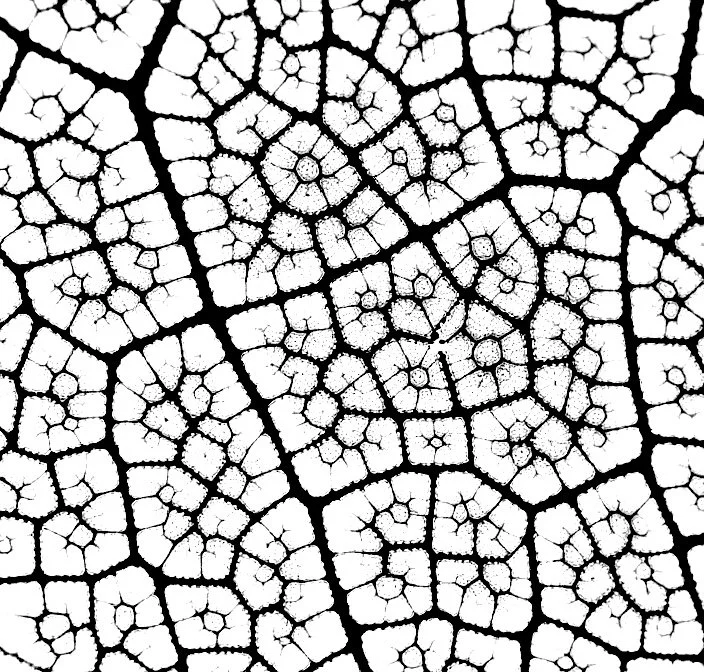

Problem Background

PLANETARY BOUNDARIES identify nine biophysical processes that regulate Earth’s stability, including climate, biodiversity, and nutrient cycles. Staying within these thresholds ensures a safe operating space for humanity, while exceeding them risks systemic collapse. This framework directly informs Sustainable Development, Doughnut Economy, and Earth4All, while providing scientific guidance for Transition Design. It also frames debates on Green Growth versus Degrowth, by highlighting limits to economic expansion. Planetary Boundaries are increasingly central to Global Governance, informing UN and EU environmental policies.

Further reading:

UN (1987): Our Common Future. Oxford University Press.

Sachs, J. (2015): The Age of Sustainable Development. Columbia University Press.

Rockström, J., et al. (2009): A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461.

Normative Foundations

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT is defined as meeting the needs of the present without compromising future generations’ ability to meet theirs. It integrates ecological integrity, social equity, and economic viability, creating a “triple bottom line” framework. It provides the normative foundation for Planetary Boundaries, the Doughnut Economy, and Earth4All, while engaging debates around Green Growth and Degrowth. Linked to Systems Thinking and Transition Design, it ensures strategies remain comprehensive and long-term. It is increasingly tied to Global Governance, as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide shared benchmarks for international action.

Further reading:

OECD (2011): Towards Green Growth. OECD Publishing.

UNEP (2011): Towards a Green Economy. UNEP.

Hickel, J., Kallis, G. (2020): Is Green Growth Possible? New Political Economy, 25(4).

Normative Foundations

GREEN GROWTH posits that economic development can continue while reducing ecological harm through decoupling GDP from emissions and resource use. It relies on innovation, renewable energy, and efficiency, closely tied to Circular Economy and Eco-Social Innovation. Critics from Degrowth argue that absolute decoupling is unachievable globally, raising tensions between paradigms. Still, green growth remains central to policy frameworks in OECD and UN strategies for Sustainable Development. As part of Earth4All scenarios, it is seen as one possible but contested pathway.

Further reading:

Kallis, G. (2018): Degrowth. Agenda Publishing.

Latouche, S. (2009): Farewell to Growth. Polity.

Hickel, J. (2020): Less is More. Penguin.

Normative Foundations

DEGROWTH calls for reducing production and consumption in wealthy countries to achieve ecological sustainability and global justice. It emphasizes sufficiency, redistribution, and new measures of prosperity, directly challenging Green Growth strategies. Degrowth aligns with Doughnut Economy, Planetary Boundaries, and Transition Design, offering systemic alternatives to growth dependency. It intersects with Development Cooperation, raising questions about fair distribution of resources and responsibilities. Degrowth also supports Wellbeing Economy visions, which aim to re-center economies on human and ecological flourishing.

Further reading:

Raworth, K. (2017): Doughnut Economics. Chelsea Green.

Raworth, K. (2020): A Doughnut for the Anthropocene. The Lancet Planetary Health.

Amsterdam Doughnut Coalition (2020): Amsterdam City Doughnut.

Normative Foundations

The DOUGHNUT ECONOMY balances Planetary Boundaries with social foundations to define a “safe and just space” for humanity. It integrates biophysical science with social equity, connecting Planetary Boundaries to Sustainable Development goals. As an applied framework, it is being tested in cities and organizations, linking to Circular Economy and Degrowth practices. It complements Earth4All scenarios and informs Transition Design by embedding justice into systemic transformation. The model is also a cornerstone for the Wellbeing Economy, operationalizing prosperity beyond GDP.

Further reading:

Club of Rome (2022): Earth for All. New Society Publishers.

Randers, J., et al. (2022): Earth4All: Turnaround Modelling Report. Club of Rome.

Jackson, T. (2017): Prosperity without Growth. Routledge.

Normative Foundations

EARTH4ALL is a global initiative (Club of Rome, 2022) modeling pathways for achieving well-being within Planetary Boundaries. It emphasizes five “extraordinary turnarounds” in poverty, inequality, empowerment, food, and energy. Earth4All aligns with Doughnut Economy, and debates on Green Growth vs. Degrowth, offering both scenarios and policy levers. It complements Strategic Foresight and Transition Design, providing narratives and metrics for global change. It also resonates with the Wellbeing Economy, framing human well-being as the ultimate policy goal.

Further reading:

Fioramonti, L. (2017): Wellbeing Economy. Palgrave.

Wellbeing Economy Alliance (2018): WEAll Vision and Values.

O’Neill, D. W., et al. (2018): A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability, 1.

Normative Foundations

The WELLBEING ECONOMY prioritizes human and ecological well-being over GDP growth as the primary measure of prosperity. It integrates health, education, equality, and environmental integrity as central indicators of success. Closely linked to Degrowth, Doughnut Economy, and Earth4All, it redefines development for the 21st century. It is supported by Creative Collaboration and Innovation Ecosystems, which design inclusive solutions for flourishing societies. The wellbeing economy also resonates with Climate Justice, ensuring transitions improve lives while reducing inequality.

Further reading:

Meadows, D. (2008): Thinking in Systems. Chelsea Green.

Sterman, J. (2000): Business Dynamics. McGraw-Hill.

Capra, F., Luisi, P. L. (2014): The Systems View of Life. Cambridge University Press.

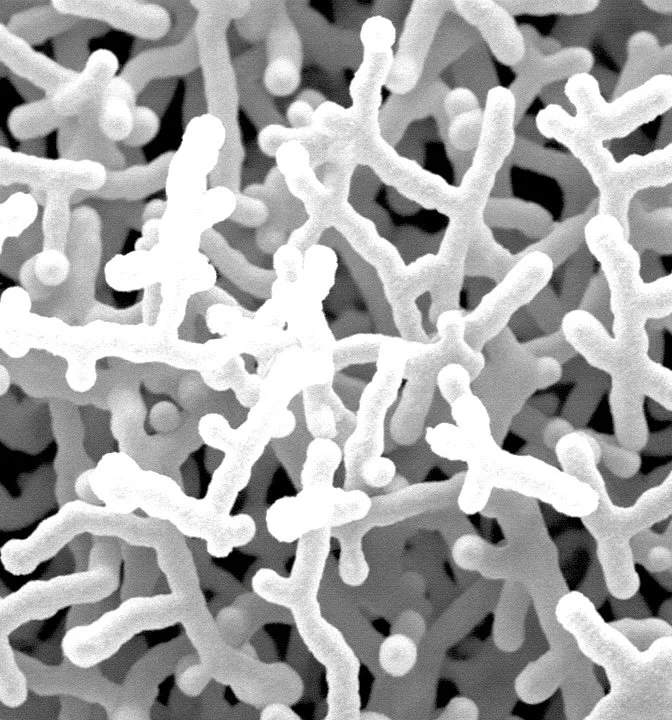

Systemic Perspectives

SYSTEMS THINKING is a way of understanding complexity by examining relationships, feedback loops, and interactions instead of isolated parts. It emphasizes nonlinearity and emergent behavior, making it well-suited to analyze “wicked problems” such as the Climate Crisis or Sustainable Development challenges. By identifying leverage points, systems thinking supports structural interventions rather than superficial fixes. It strongly underpins Resilience Thinking, Circular Economy, and Transition Design, enabling holistic and adaptive responses. It also connects with Global Governance, providing a shared framework to coordinate policies across scales.

Further reading:

Holland, J. (2014): Complexity: A Very Short Introduction. OUP.

Mitchell, M. (2009): Complexity: A Guided Tour. OUP.

Snowden, D., Boone, M. (2007): A Leader’s Framework. Harvard Business Review.

Systemic Perspectives

COMPLEXITY THEORY examines systems with nonlinearity, self-organization, and emergent properties, while adaptive systems emphasize feedback and learning. This lens helps explain why traditional, linear solutions often fail in contexts such as the Climate Crisis or Sustainable Development. Closely tied to Systems Thinking and Resilience Thinking, it also informs Innovation Ecosystems and adaptive governance. Complexity perspectives strengthen Strategic Foresight, which must account for unpredictable dynamics when exploring futures. They also inform Global Governance, which increasingly requires adaptive, polycentric structures.

Further reading:

Folke, C., et al. (2010): Resilience Thinking. Ecology & Society, 15(4).

Walker, B., Salt, D. (2006): Resilience Thinking. Island Press.

Gunderson, L., Holling, C. (2002): Panarchy. Island Press.

Systemic Perspectives

RESILIENCE THINKING focuses on how systems can absorb shocks, adapt, and transform in response to stresses and crises. It emphasizes adaptive cycles, thresholds, and diversity, offering a framework for navigating uncertainty in socio-ecological systems. Strongly linked to Systems Thinking and Complexity Theory, resilience guides strategies for climate adaptation and governance. It connects with Transition Design, Planetary Boundaries, and Eco-Social Innovation, which all emphasize systemic adaptability. In the context of Climate Justice, resilience approaches must ensure vulnerable communities are prioritized.

Further reading:

Sanders, E., Stappers, P. (2008): Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1).

Martin, B., Hanington, B. (2012): Universal Methods of Design. Rockport.

Koskinen, I., et al. (2011): Design Research Through Practice. Morgan Kaufmann.

Methodological Approaches

DESIGN RESEARCH generates knowledge about user practices, social contexts, and material environments to guide design processes. It integrates ethnography, participatory methods, and prototyping to reveal both expressed and hidden needs. As a foundation for Design Thinking, it ensures solutions are grounded in real-world practices rather than abstract assumptions. It also strengthens Participatory Design and Eco-Social Innovation, ensuring legitimacy and inclusivity. By connecting to Climate Justice, design research ensures marginalized voices are actively included in design processes.

Further reading:

Schuler, D., Namioka, A. (1993): Participatory Design. Erlbaum.

Spinuzzi, C. (2005): Methodology of Participatory Design. Technical Communication, 52(2).

Simonsen, J., Robertson, T. (2013): Handbook of Participatory Design. Routledge.

Methodological Approaches

PARTICIPATORY DESIGN involves stakeholders directly in shaping design outcomes, ensuring inclusivity, ownership, and democratic legitimacy. Originating in Scandinavian workplace democracy, it now informs urban planning, ICT, and sustainability transitions. It complements Design Research, Creative Collaboration, and Stakeholder Engagement, making it central to building trust and relevance. In Eco-Social Innovation and Development Cooperation, participatory methods ensure marginalized voices are heard in creating systemic change. It also strengthens Climate Justice efforts by involving vulnerable communities.

Further reading:

Brown, T. (2009): Change by Design. Harper Business.

Liedtka, J., Ogilvie, T. (2011): Designing for Growth. Columbia University Press.

Carlgren, L. (2016): Design Thinking as an Enabler of Innovation. Chalmers University.

Methodological Approaches

DESIGN THINKING is an iterative, human-centered approach to problem solving that combines empathy, creativity, and rationality. It focuses on understanding user needs, framing challenges, ideating broadly, and rapidly prototyping solutions. Closely linked to Design Research (for insights) and Creative Collaboration (for teamwork), it provides methods for innovation in business, policy, and social contexts. When embedded in larger frameworks like Systems Thinking, Eco-Social Innovation, or Sustainable Development, design thinking moves beyond products to shape transformative change. It also plays a role in Wellbeing Economy initiatives by designing services and policies that prioritize quality of life.

Further reading:

Sawyer, R. (2007): Group Genius. Basic Books.

Hargadon, A. (2003): How Breakthroughs Happen. Harvard Business School Press.

Mattelmäki, T., et al. (2014): What Happened to Empathic Design?. Design Issues, 30(1).

Methodological Approaches

CREATIVE COLLABORATION emphasizes co-creation across disciplines, sectors, and cultures to solve complex problems collectively. It relies on diversity, dialogue, and shared vision, complementing Design Thinking and Participatory Design. In innovation networks, it links to Innovation Ecosystems, while in sustainability contexts, it supports Eco-Social Innovation and Transition Design. Collaborative creativity is vital in tackling the Climate Crisis, where solutions require inclusive, systemic, and globally coordinated action. It also underpins Wellbeing Economy approaches by mobilizing collective intelligence.

Further reading:

Bryson, J., et al. (2013): Designing Public Participation. Public Administration Review.

Reed, M. (2008): Stakeholder participation. Biological Conservation, 141.

Freeman, R. (1984): Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman.

Methodological Approaches

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT ensures diverse voices and actors are included in processes of decision-making, governance, and transformation. It emphasizes inclusivity and legitimacy, making it central to Participatory Design, Eco-Social Innovation, and Innovation Ecosystems. Engagement strengthens Transition Design and Sustainable Development, which require multi-actor cooperation. It also supports Development Cooperation, making global interventions more equitable and locally relevant. As Climate Justice becomes a global priority, stakeholder engagement is indispensable.

Further reading:

Dunne, A., Raby, F. (2013): Speculative Everything. MIT Press.

Malpass, M. (2017): Critical Design in Context. Bloomsbury.

Auger, J. (2013): Speculative Design. Digital Creativity, 24(1).

Methodological Approaches

SPECULATIVE AND CRITICAL DESIGN explore alternative futures by creating provocative artifacts, narratives, and scenarios that question assumptions. Instead of solving problems, they provoke debate on cultural, ethical, and technological issues. They are closely linked to Strategic Foresight, Creative Collaboration, and Transition Design, which use them to expand imagined futures. In contexts such as the Climate Crisis or Planetary Boundaries, speculative design can expose unintended consequences of current trajectories. It also complements Wellbeing Economy debates by envisioning futures beyond GDP-driven paradigms.

Further reading:

Voros, J. (2003): A generic foresight process framework. Foresight, 5(3).

Hines, A., Bishop, P. (2015): Thinking about the Future. Hinesight.

Miller, R. (2018): Transforming the Future. Routledge.

Methodological Approaches

STRATEGIC FORESIGHT is the structured practice of exploring multiple possible futures to build preparedness and resilience under uncertainty. Rather than predicting one trajectory, it develops scenarios, identifies weak signals, and analyzes trends to anticipate disruptive change. It is particularly effective when combined with Systems Thinking, Transition Design, and Design Thinking. In tackling the Climate Crisis, foresight enables decision-makers to identify leverage points and avoid lock-ins. As part of Global Governance, foresight supports collective anticipation and coordination of cross-border challenges.

Further reading:

Irwin, T., Kossoff, G., Tonkinwise, C. (2015): Transition Design. Design Philosophy Papers, 13(1).

Fry, T. (2009): Design Futuring. Berg.

Escobar, A. (2018): Designs for the Pluriverse. Duke University Press.

Transformative Frameworks

TRANSITION DESIGN addresses the long-term, systemic changes required to shift societies toward sustainable futures. It emphasizes the creation of new infrastructures, lifestyles, and governance systems aligned with ecological and social well-being. Building on Systems Thinking, Strategic Foresight, and Sustainable Development, it offers frameworks for navigating transformative change. It also intersects with Degrowth, Eco-Social Innovation, and Earth4All, which provide visions for post-growth futures. Transition design is crucial for a Just Transition, ensuring changes are socially inclusive and equitable.

Further reading:

Moulaert, F., et al. (2013): International Handbook on Social Innovation. Edward Elgar.

Murray, R., et al. (2010): The Open Book of Social Innovation. Nesta.

Howaldt, J., Schwarz, M. (2017): Social Innovation. Springer.

Transformative Frameworks

ECO-SOCIAL INNOVATION integrates ecological sustainability and social justice in new practices, models, and policies. It is rooted in collective creativity and collaboration, often drawing on Participatory Design and Creative Collaboration to ensure inclusivity. By aligning with Circular Economy, Doughnut Economy, and Degrowth, eco-social innovation emphasizes systemic shifts over incremental fixes. It thrives at the intersection of Sustainable Development and grassroots experimentation, bridging local action with global impact. It also plays a role in Just Transition, where innovation is required to ensure that ecological change benefits vulnerable communities.

Further reading:

Mang, P., Reed, B. (2012): Designing from Place. Building Research & Information, 40(1).

Lyle, J. T. (1994): Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development. Wiley.

Cole, R. J. (2012): Transitioning from Green to Regenerative Design. Building Research & Information, 40(1).

Transformative Frameworks

REGENERATIVE DESIGN seeks not just to sustain but to renew ecological and social systems by aligning human activity with natural processes. It emphasizes co-evolution, place-based approaches, and creating systems that strengthen rather than deplete ecosystems. It connects directly with Circular Economy and Sustainable Development, and extends the ethical commitments of the Planetary Boundaries framework. By supporting Transition Design and Resilience Thinking, it offers practices that restore rather than merely preserve. Regenerative design also resonates with Wellbeing Economy goals by linking ecological vitality with human flourishing.

Further reading:

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2019): Completing the Picture.

Stahel, W. (2016): The Circular Economy. Nature, 531.

Geissdoerfer, M., et al. (2017): Circular Economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 143.

Transformative Frameworks

The CIRCULAR ECONOMY replaces the linear “take–make–dispose” model with regenerative loops of reuse, recycling, repair, and resource efficiency. It provides practical solutions for achieving Green Growth, while also supporting Degrowth and Doughnut Economy approaches that emphasize sufficiency. As part of Sustainable Development, it helps align industries with planetary limits, and it strengthens Innovation Ecosystems that enable cross-sector collaboration. Through Systems Thinking, circular models reveal how resources can flow more sustainably through society. Circular practices also link to Just Transition by creating green jobs and reducing inequalities.

Further reading:

Adner, R. (2006): Match Your Strategy to Your Ecosystem. Harvard Business Review.

Granstrand, O., Holgersson, M. (2020): Innovation ecosystems. Technovation.

Jackson, D. (2011): What is an Innovation Ecosystem?. NSF.

Transformative Frameworks

INNOVATION ECOSYSTEMS are networks of interdependent actors—firms, governments, research institutions, and communities—that co-create and exchange knowledge. Unlike linear innovation, ecosystems thrive on collaboration, diversity, and shared infrastructures, aligning with Complexity Theory. They link directly to Creative Collaboration, Eco-Social Innovation, and Circular Economy, supporting transformative change across scales. Effective ecosystems rely on Stakeholder Engagement to balance interests and enable trust. As sustainability becomes central, ecosystems play a role in advancing Earth4All and Wellbeing Economy agendas.

Further reading:

Easterly, W. (2006): The White Man’s Burden. Penguin.

Sachs, J. (2005): The End of Poverty. Penguin.

Moyo, D. (2009): Dead Aid. Penguin.

Political and Governance Perspectives

DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION includes financial, technical, and institutional support aimed at reducing poverty and fostering sustainable growth in the Global South. It has shifted from aid dependency to partnerships emphasizing local ownership, resilience, and sustainability. It connects with Sustainable Development, Participatory Design, and Stakeholder Engagement, ensuring solutions are contextually grounded. In the context of the Climate Crisis, development cooperation increasingly funds adaptation and mitigation in vulnerable countries. Debates on Degrowth and Climate Justice also challenge cooperation models by stressing fairness and redistribution.

Further reading:

Held, D., Koenig-Archibugi, M. (2005): Global Governance and Public Accountability. Blackwell.

Biermann, F., Pattberg, P. (2012): Global Environmental Governance Reconsidered. MIT Press.

Hale, T., Held, D., Young, K. (2013): Gridlock. Polity.

Political and Governance Perspectives

GLOBAL GOVERNANCE refers to the collective management of transboundary issues like climate change, biodiversity, and inequality through institutions, agreements, and networks. It includes formal structures such as the UN and informal mechanisms like global partnerships. It is deeply tied to Sustainable Development (via SDGs), Planetary Boundaries, and Climate Crisis management, while engaging with Earth4All and Wellbeing Economy visions. Effective governance requires Stakeholder Engagement and recognition of Climate Justice principles to ensure legitimacy. It also benefits from Systems Thinking and Complexity Theory, which highlight the adaptive and multi-level nature of governance.